Justin Cartwright (1960W) | 1943 - 2018

We regret to announce that Justin Cartwright died on Monday 3rd December 2018 in London, where

he lived.

An obituary was written by his brother, Tim:

Justin Cartwright, who has been described as “South Africa’s most successful recent literary export”, died in London on 3rd December. He was 75 years old. For some two years, he had been plagued by an Altzheimer type illness which affected his brain but not, initially, his body. He found it more and more difficult to remember facts and commitments and later even to recognize people he had lived with or known for years—but his sons have said that, as far as they could judge, he did not fully realize what was happening and therefore did not suffer unduly.

Justin was at Bishops for a full ten years, always as a boarder. This was because his mother contracted a lung disease which necessitated her moving to Cradock to “dry out” and she took with her both her sons, the other being Tim, three years older than Justin, who also had a full ten years at Bishops. The boys’ father, Paddy Cartwright (i.e. the author AP Cartwright), who was also an OD, was convinced that Bishops was the only school for his sons and so there they stayed even after their mother was cured and moved to Johannesburg to rejoin their father. After returning from war service he edited “The Countryman”, then moved on to become an acting editor and later editor of The Rand Daily Mail but, like three subsequent editors, was eventually “retired”. (The RDM at that stage had significant losses but played the leading role in SA media in challenging the Apartheid government.) APC moved on to write 19 books, all non-fictional and covering SA subjects, notably the gold mining industry, which he was able to humanise by relating in detail the challenges and triumphs of the industry’s initiators. Justin, therefore, grew up in a household where writing was thought to be the normal way of life, even though it could be demanding.

Justin was never atypical Bishops boy but he always acknowledged that the school had taught him to think for himself and to reject commonly held prejudices. He was always near the top of this class and a good rugby centre and track sprinter. Later he played for his college at Oxford and even became something of an American Football star when, after matriculating, he had a year in Michigan as an American Field Service scholar.

Back in SA after this year in the USA he read for and obtained a BA, his major subjects being Politics and French. It was here he first emerged as a writer, producing amusing lampoons on student life and politics. He had a host of friends and, if the reports are accurate, was “always good at a party”.

He then fulfilled a lifelong ambition by getting into Oxford, where he took a PPE related D. Litt, his subject being the political philosophy of Oliver Cromwell. As he and Tim, had been brought up with horses, he was somehow able to get into the Oxford polo team, which was largely sponsored by the (female) captain’s wealthy family business. During the long Summer vacations, he worked as a guide for a large American company which offered package tours of Europe and it was his earnings from this that (just) enabled him to buy and keep a polo pony. Later Justin wrote “The Secret Garden”, a book of nostalgic memories ( and some serious analyses of the whole institution) about his time at Oxford. This revealed just why so many Oxford students grew to love and respect the place—and it is quite possibly his most appreciated book. It probably helped him to be made a fellow of his old college, Trinity, an honour that he very much appreciated.

On graduating he went into advertising in London, focusing much of the time on filmed commercials. He won at least one major award for a dog food commercial. His firm also won the account for the Liberal party and later the SDP-Liberal Alliance and he wrote political broadcasts for them for three elections and by now he was more or less certain he wanted to stay in the UK forever. He was awarded an MBE for his political work.

His main interest had long been fictional writing and it was inevitable that he would eventually turn to this as a way of life. He was influenced by two American writers, in particular, Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, both not much in favour with those with conservative tastes in literature. There is today some argument about what was his first book because his early works do not make it on to his CV, but he did do “The Horse of Darius”, a thriller set in Iran under the Shah at the start of the revolution; and a novel, “Freedom for the Wolves”, which he later decried as not up to the standard he had strived for—but he was learning and improving all the time.

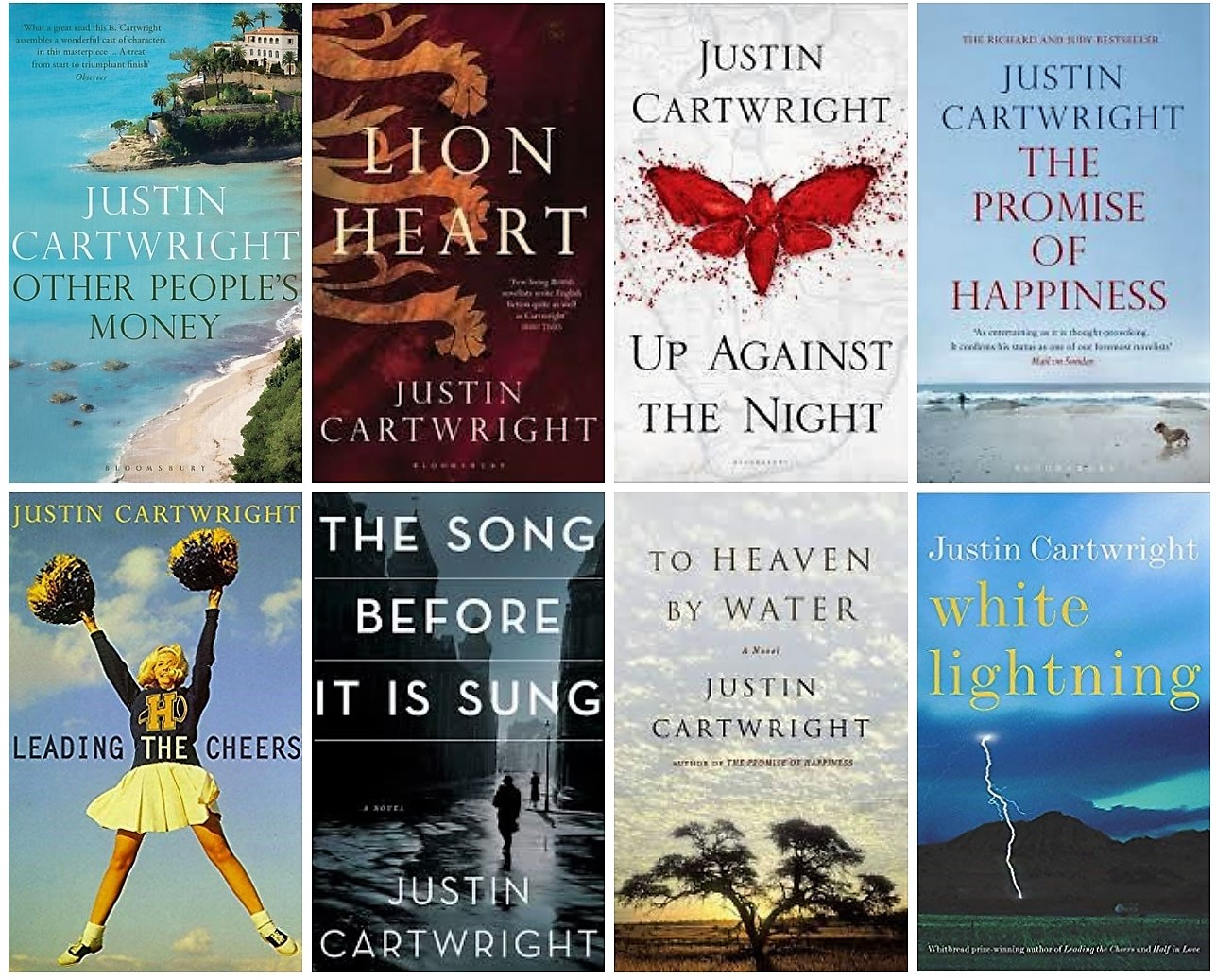

Over the following years, he turned out novels and other works at a rate of about one a year. One of the first to get complimentary reviews was “Interior” which tells of a quest by the son of a National Geographic journalist who goes in search of his father who has disappeared in Central Africa. It is probably true, however, as at least one reviewer has commented, that Justin’s great strength lay in depicting the psychological and other forces at work in typical, intelligent, modern middle-class British families. Several of the central characters are middle-aged, supposedly successful men who, for no apparent reason, are disillusioned or slightly jaded. In “Other Peoples’ Money” a slightly shady deal by a respected investment consultant has serious repercussions and in “The Promise of Happiness” a much-loved daughter is sent to jail in the USA for an art fraud deal for which she was not really responsible. In “Half in Love” a high-placed politician falls in love with a surprisingly genuine top actress and gets fed up with politics. However, as Justin by no means confined his attention to the UK, his novels take the reader time and again back to Africa (“Masai Dreaming”, set in Kenya, proved to be one of his most liked novels and his last book before he got ill, “Up against the Night” is at least in part about Piet Retief to whom he was related through his maternal grandmother). He often has action in France under the German occupation and in Germany at the time of the aristocrats’ and generals’ plot to assassinate Hitler (The Song Before It Is Sung”), while “Leading the Cheers” is set in the USA and gives a portrait of a mid-west society there that a reviewer has called uncannily true to life. Palestine and the Holy Land feature strongly in two of his novels, especially “Lionheart”, a historical account of Richard II’s crusades.

Starting from fairly humble beginnings as a novelist, Justin set himself the goal of being “the finest living exponent of the English language”. What is certain is that his time at Oxford exposed him to many whose thought and style were subtle and elegant and worthy of emulating—which he did. And there are some who DO believe he obtained the goal he set himself.

Justin leaves a wife Penny who is a special skills teacher looking after children with learning disabilities, and two sons, both married, one a medical doctor and surgeon specialising in research and the other who lives in Spain and works for TV networks as a journalist. There are four grandchildren. He also leaves his only brother, Tim.

Read more about Justin on his Wikipedia Page