Jan Smuts and Bishops

Jan Smuts paid a visit in 1927 to Bishops in order to unveil the War Memorial bronze plaque over the main door of The War Memorial Chapel.

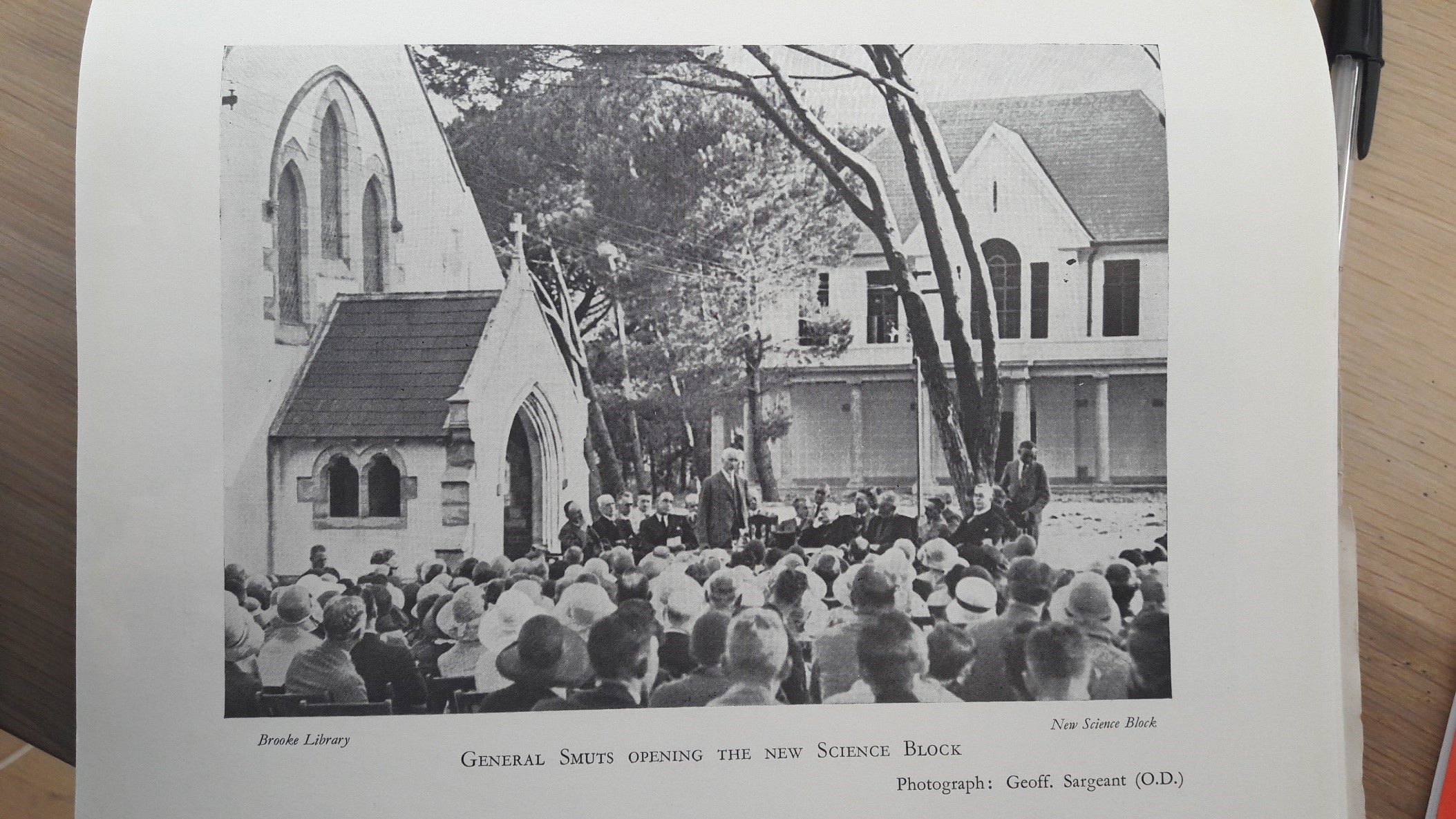

He was back on the 4

th February 1932 to open the New Science Block.

And there is yet another, longer lasting link between Bishops and Smuts….

DC Magazine September 1960, p. 31:

“

Doornkloof, Irene, Transvaal: Last June, Guy Brathwaite (1926-30), who practises in Pretoria, bought the historic rambling old wood and iron homestead of the late General Smuts and the surrounding 25 morgen of land. The property, which will be restored and preserved as a monument to one of the Commonwealth’s greatest sons, is to be administered by the trustees of the newly formed Jan Smut’s War Veteran’s Association which will include at least one representative of each of the Cape Coloured Corps and the Native Military Corps. Brathwaite, first trustee of the Association, has great plans for the future of the property. He hopes that in time it will become a rallying place where South Africans of all races and sections will rediscover the spirit of unity. Later in the Magazine there is a special article by Brathwaite on “Why I Bought the Smuts Family’s Home”.

That article appears on the same edition of the DC Magazine on p.46:

WHY I BOUGHT THE SMUTS FAMILY’S HOME

By Guy Brathwaite (1926-30)

The following is reprinted with acknowledgement to the Johannesburg

Star in which it was published on the 14

th July, 1960. Brathwaite is prominent in Pretoria where he is a partner in the legal firm of Adams and Adams. His two O.D. sons are students at Stellenbosch University.

“When General Smuts died in 1950 most of the members of his family, who by that time had families of their own, thought that Mrs. Smuts should leave the old house at Irene and live somewhere more convenient.

But Isie Smuts said ‘No’. She had lived at Doornkloof for 40 years and it was ‘home’. What was more it was stacked with an accumulation of books and papers that filled every cupboard, to say nothing of rows of boxes and chests, throughout the house.

Only she knew where everything was. Only she could ‘tidy up’.

The house- the ‘Big House’ the Smuts family called it- was at that time a historian’s treasure chest. General Smuts all his life had kept up a correspondence with famous men in all parts of the world.

They wrote to him. He replied, and an exchange of letters followed. All these letters he had kept.

People sent him papers, presents, decorations, tokens of their esteem, illuminated addresses, books. Having read or examined these things he would say: ‘Ouma, let’s put this somewhere.’

And Ouma’s own filing system then went into action. A place was found for everything that had to be kept. When Ouma died in 1954 there was a tremendous amount of sorting out to be done, and various relics of the great man went this way and that.

You will remember that it was then suggested that the house should be preserved as a national monument to the greatest of all South Africans.

Most of us who had known Smuts, served under him and admired him, thought that this was a splendid idea. We did not know quite what form the memorial should take, but it seemed right that the house in which he had lived and where some of South Africa’s historic meetings had been held, should be preserved.

Then for a period of four years there was talk but nothing happened. Some said this and some said that.

It was ‘only an old wood-and-iron-house’… It would cost a fortune to restore…

Was this really the right sort of memorial to Smuts? ... Would not a statue be more appropriate?

Nobody seemed willing to accept the responsibility for the plan. No official body was interested. Nobody did anything.

And in the meantime the old house was going to rack and ruin.

It had always seemed to me that there could be no more appropriate memorial to Smuts than this unpretentious building, which he had bought from ‘the enemy’ of the South African War, afterwards his allies, and which had been his only home for the greater part of his life.

I thought of the hundreds of thousands of men and women in Great Britain, in the United States, the Commonwealth, and Europe, who have been brought up to regard him as one of the great men of the 20

th century.

‘When they visit South Africa, as more and more of them will do as the years go by, they will want to see the simple house in which he lived,’ I said to myself. ‘They will be prepared to make a pilgrimage to Pretoria just to visit the old house.’

It seemed to me absurd to say that it was not worth preserving just because it was a wood-and-iron structure. Its very simplicity was exactly what made it an appropriate memorial to the man.

A brick and plaster mansion would have been ‘ordinary’. This old military building, originally an officers’ mess in the South African War, perfectly illustrates Smuts’s indifference to luxury and ease of living.’

He was above such things. It never occurred to him to build a mansion though he could well have afforded to do so. He wanted a house ‘where the veld came right up to the front door.’

Also there were the ex-servicemen of South Africa, 200 000 strong. They wanted a memorial to their leader, the Field-Marshal who remained a General to his troops and was even better known as ‘the Oubaas’. What finer memorial could they ask than his old home?

My ideas on what might be done with the house had reached this point when I heard that all plans for preserving Doornkloof had fallen through, that it would be sold to private interests which hoped to develop the land.

Somebody had to act and act quickly. After some heart-searching and a brief consultation with my co-Trustees of the Gunners’ Association, I bought the house and 25 morgen of the surrounding land.

This had to be a personal transaction. There was no time for anything else.

I am thus the nominal owner of Doornkloof at the moment. But I have already laid plans for a Jan Smuts War Veterans’ Foundation which will hold the property in trust in perpetuity for the nation and for ex-servicemen.

This foundation will eventually administer the property and turn it into a national monument which we know will become a place of pilgrimage and a fitting memorial to the Oubaas.

From all corners of the Union have come letters offering me the support and assistance, not simply of ex-servicemen, but of people in all walks of life.

All I can say at the moment is that ‘where there is a will there is a way’. As soon as we have settled the administrative details we shall set to work to restore the Big House. I promise that, within a year, it will no longer look old and dilapidated but will have acquired all the spit and polish that is the Army’s speciality.

After that we shall plan the re-furnishing of the house (eventually it will bear a very close resemblance to the old Smuts home), the lay-out of the grounds – possibly an ex-servicemen’s hall, and possibly an interdenominational chapel.

We believe that, when this is done, most South Africans and thousands of people from all parts of the world will beat a path to the door of the old house that was once the home of a great statesman.”